This is from the "archives" - written ten years ago about something that happened twenty-five years ago...

There

is something about the magical power of a Eurail pass that causes it

to burn in your pocket, like a gleaming quarter handed to a four year

old. You want to use the thing and you want to use it often. The side

effect is that all this moving around leaves very little time in each

destination, but in fact this need not be a problem at all, as my

friend Mark and I demonstrated one summer. We had already dispatched

with Paris and Nice in a matter of a few hours each and were now

rolling towards Venice.

The

approach by train into Venice is only remarkable in its profound

dullness and in that it gives no hint whatsoever of what is to come.

However, the minute you step out of the front doors of the train

station, you know where you are. Rather than the usual frenzied

Italian scene of buses and mopeds and honking and fumes there is a

great sweeping set of broad stone steps leading down to the Grand

Canal where the vaporetti (water buses) lie bobbing.

The

good fortune of Venice is that its Golden Age of wealth and lavish

spending on architecture was mercifully followed by a rapid descent

into obscurity, which ensured its preservation, like a fly trapped in

amber. These days Venice is of course anything but obscure. Many

people are frightened off by this popularity, fearing a nasty theme

park atmosphere - a kind of Disney-On-The-Canals populated by cynical

locals and sweaty throngs of braying tourists. This nightmare

certainly exists in spots, but we found that it could be easily

evaded as well.

The

instinct upon arrival is to trot right on down those grand steps and

make for the nearest vaporetto for a cruise down the Grand Canal to

the Piazza San Marco. Infinitely more agreeable, however, is the

land-route, which begins at a little bridge a few steps off to the

left. There are signs marking the way, but they are small –

evidently too small for most people. One minute: those braying sweaty throngs. The next minute: a deserted lane wending between stylishly

decayed 15th

century villas.

It

took us almost two hours to reach the Piazza San Marco in this

fashion and I easily count them among my best two hours of travel

anywhere. The route took us alongside slender canals, over tiny

arched stone bridges and across a profusion of little plazas and

squares. Some of these squares were fronted by grand buildings and

churches that were clearly of significance, but others featured only

graffiti and scraps of litter spinning in slow vortexes created by

isolated eddies of wind. I found the graffiti and litter oddly

comforting; an affirmation I suppose that Venice was a real place,

not just a carefully primped outdoor museum.

The

signs marking the way were well placed: they were unobtrusive and

always put just at the point where you began to wonder whether

perhaps you had taken a wrong turn and gone astray. This allowed for

a pleasant sensation of mild adventure as we slowly threaded the

labyrinth. The stillness of the place was remarkable. There were few

Venetians about and fewer still tourists. Those tourists we did meet

were invariably middle aged Germans earnestly examining some

architectural detail while referring to their encyclopedic guidebooks.

The

midway point of the walk is the famed Rialto Bridge. After the Piazza

San Marco and the Grand Canal, this bridge is probably Venice’s

best-known feature. Built in 1588 it was the first permanent crossing

of the Grand Canal, linking the two halves of Venice. It has a very

distinctive appearance with shops running up both sides, backed by

tall arches. The bridge is steep enough to require stairs to reach

the middle where the shops give way to a pleasing, albeit perpetually

jam-packed, vantage point over the canal. Pretty from a distance, up

close it is festooned with purveyors of

knick-knacks and enough obese tourists to give you pause to wonder

whether 16th

century structural engineering calculations could in any way

anticipate the girth and heft of the average 20th

century sightseer. We elbowed our way across and a few minutes later

- poof

- as in a fairy tale wish: all was peace and emptiness again.

We

ambled along contentedly again until the gradual increase in the

number of shops signalled that we were approaching the epicentre, the

Piazza San Marco, or St. Mark’s Square. First though, a word about

these shops. Evidently there are only three types of businesses in

Venice, with each type being roughly equal in prevalence.

Fully

one third of the shops devoted themselves to glassware. When I say

glassware I do not mean beer mugs and chemistry beakers and other

such useful objects, but bizarre coloured baubles and trinkets and

exceptionally impractical looking vases. There were scores of such

shops, often one right after the other, resulting in an effect that

was both dazzling and monotonous at the same time. To be fair, Venice

does have a long tradition of glassblowing, so aficionados of

demented looking pink and green glass animals from all around the

world know precisely where to come, but the backpacker is not well

served. Thin hand-blown glassware is about as sensible a souvenir to

have rattling about in one’s pack as live quail or unexploded

ordinance.

The

next third were similarly useless: Carnival mask boutiques. Much as

with the glassware emporia, there were scads of these, selling

nothing but papier-mâché Carnival masks. It’s a shame really that

what was once an appealing tradition has been reduced to a basement

rec room decorating standby on the level of the bamboo fan painted

with the hot pink tropical sunset.

A

brochure describing the Venetian Carnival during the Middle Ages

professed rather breathlessly:

“Masked

courtesans would participate in the most wanton games of lust, and

confident of their anonymity would shed all conventional inhibitions.

Noblemen, who would normally take painstaking care not to divulge a

hint of their sexual preferences, could perform in mask acts that at

the time were considered immoral and illegal.”

Cool.

Moreover, “Carnival” in those days lasted from December 26 until

Shrove Tuesday – over three months! Masking was also encouraged for

a period during the fall and again in early summer. Those wanton

Venetians. After the so-called Serene Republic (doesn’t seem so

serene anymore, does it?) fell on hard times the party was over, both

figuratively and literally. Ultimately Carnival was even banned

because of an unseemly number of fatal mishaps. I could not find

detailed descriptions of these “mishaps”, but it’s easy enough

to imagine what transpires when alcohol, masks, wantonness and canals

are thrown together. Carnival was revived in the 1970s by the

government as an annual one-week fleecing of tourists during

February. It is now Venice’s biggest yearly draw and provides an

interesting counterpoint to Rio’s now more famous festivities. The

Brazilians have stayed true to the medieval Carnival ideals of lust,

excess and craziness, whereas, at least according to the ubiquitous

postcards of dark cloaked figures with eerie white masks stalking

alongside mist-shrouded canals, Venice’s Carnival now looks

disappointingly austere and intellectual.

In

any case, neither of us were the target demographic for the mask

vendors. The final group of Venetian shops did, however, hit the

mark. Stationers. Stationers by the dozen. And not, I might add, your

standard Office Depot or Staples either. These were dimly lit little

warrens, furnished in the darkest, richest wood and crammed full with

luxurious cream-coloured velum, bricks of deep red sealing wax, black

and gold pens that cost as much as a major appliance and an

eye-popping assortment of antique brass and wooden gadgets –

everything the discriminating European aristocrat could want for the

sprawling oaken desk in his castle tower office. We pawed through

these goods, relishing the smells of ink and leather and old wood,

but there was nothing either of us could afford. Well ok, I

probably could have managed a few envelopes, but when you’ve lusted

after an antique desktop globe with a handsome carved wooden stand

for $2250, it’s absolutely not possible to be satisfied with

anything less.

Evidently

anyone in search of a crescent wrench, toilet paper or a sack of

potatoes in Venice was out of luck.

We

were in the midst of this engaging session of window-shopping when,

with startling abruptness, one of the little lanes spat us out onto

the Piazza San Marco. There she was, an expanse of cobbles encrusted

with pigeon shit, lined on three sides by some rather anonymous

looking Renaissance buildings and on the fourth by the unarguably

magnificent St. Mark’s basilica. No doubt some of these “anonymous”

buildings were actually of tremendous importance, but

blessed by our ignorance we ignored them and made straight for the

obvious target, the basilica.

Mark

was wearing shorts, but had had the foresight to bring a pair of long

pants along, so before the guards could pick him up and caber-toss

him out onto the square, he nipped around the corner and pulled his

long pants up over his already bulky shorts. This gave him the

appearance of a man with explosives strapped to his posterior, but

that failed to interest the guards and we were admitted without so

much as a bored glance.

Now

this was an impressive church. St. Marks was the first cathedral we

had seen with a strong Byzantine influence. Immediately upon entering

we found ourselves in a kind of foyer under a series of domes that

were completely covered with gold tile mosaics. This had the effect

of creating a roomful of upturned faces and rigorously craned necks.

We joined the hundred or so tourists already wedged into this space

and gaped awestruck at what was above us. The mosaics had that

Eastern Orthodox look about them that one associates with Russian

icons, although Venice always has been Roman Catholic. We presumed

that the story being illustrated above was that of the virtuous life

and abundant miraculous deeds of St. Mark, but it was difficult to be absolutely certain on that point as there was quite a bit going on up

there and all the figures wore similarly beatific expressions.

The

mosaics in the foyer were apparently just an aperitif - in the aircraft hanger sized main chapel there were

acres of gold mosaics in the high domes, on the columns, in the

niches, everywhere… The altar-screen was something else too - it was entirely

encrusted in jewels and enamel icons. Apparently St. Mark himself, or

at least some representative sampling of his body parts, was here

somewhere too. His original resting place was Alexandria, Egypt, but

two enterprising Venetian merchants dug him up and smuggled him here

as, much in the fashion of modern boomtowns that lure sports

franchises from more stagnant cities, they felt that their

up-and-coming town deserved an A-list saint. We meandered about for a

short while like stunned cattle and then, suddenly overcome by a

powerful craving to buy souvenirs, made for a stand we had seen in

the foyer. This was a restrained and tasteful affair – no

Pope-On-A-Rope or “To Hell With Satan” t-shirts here, only books,

postcards and a few small curios.

Disappointed,

we wandered back out onto the piazza. Mark still looked like he was

trying to shoplift a tablecloth, so he took off his long pants and

then we set about the serious business of getting the requisite

pictures of each of us feeding the pigeons in the middle of the

square with St. Mark’s Basilica forming the scenic backdrop. We

didn’t actually have any food for the pigeons, but not being

possessed of an especially keen intellect they allowed themselves to

be faked out repeatedly until we got a few nice shots.

Although

the basilica is clearly the star of the piazza, one’s eye is also

drawn to the bell tower associated with Doge’s Palace, one of the

otherwise undistinguished buildings marking the perimeter of the

square. This tower is quite tall and its pointy roof dominates the

Venetian skyline. It stands just kitty-corner from the basilica and

is traditionally something a visitor would climb in order to gain a

view of the city from above. We looked at it for a moment and

reflected on how ridiculous the word “Doge” sounded, like a

six-year-old boy saying “dog” when he’s in a silly mood. In

fact it’s just “duke” in the local dialect, but considerably

more fun to say.

Mark

looked at me, “Doge.”

“Doge,”

I shot back.

“Doge!”

“Doge!”

“Double

Doge!”

Well,

you get the picture. And with that our time was up. The tower was

going to be too expensive to climb anyway, so we trotted down to the

dock and located a vaporetto headed in the direction of the train

station.

The

profusion of boat traffic on the Grand Canal created a disagreeable

chop, so the boat rocked perilously as we tried to jump aboard. The engine sounded like a concerto of one hundred chainsaws with

guest accompaniment by a quartet of wood-chippers. I had actually

been looking forward to this ride along the Grand Canal as a scenic

cruise of sorts to cap our visit to Venice, but the sickening motion,

the noise, the nasty fumes and the fact that we were packed in like

Tokyo subway commuters diminished the pleasure somewhat. I spent the

trip wedged in such a way that my view was dominated by a man’s

right ear. It was an outstandingly hairy ear and as such was mildly

interesting, but I am confident that I did not need to go all the way

to Venice to see that. Otherwise though, the trip had been entirely

worthwhile. Four hours in Venice and, to quote Sir Edmund Hillary,

“we knocked that bastard off”. Next stop Vienna; it’s bigger,

so maybe six hours?

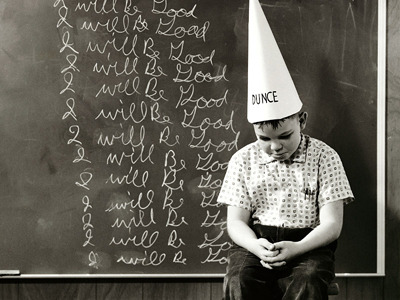

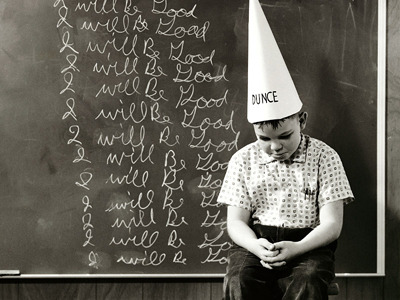

This then got me thinking about dunce caps. For those of you too young or too innocent, dunce caps were tall conical hats with a "dunce" or simply "D" written on them that especially slow or misbehaving children were forced to wear while seated on a special stool in the classroom as a kind of shaming. Although I was in grade school long enough ago to have had a school principal who actually kept a leather strap in his desk drawer that he was not only legally permitted to use on children but positively encouraged to, I was at least a couple generations too late for the dunce cap.

This then got me thinking about dunce caps. For those of you too young or too innocent, dunce caps were tall conical hats with a "dunce" or simply "D" written on them that especially slow or misbehaving children were forced to wear while seated on a special stool in the classroom as a kind of shaming. Although I was in grade school long enough ago to have had a school principal who actually kept a leather strap in his desk drawer that he was not only legally permitted to use on children but positively encouraged to, I was at least a couple generations too late for the dunce cap.

This then got me thinking about dunce caps. For those of you too young or too innocent, dunce caps were tall conical hats with a "dunce" or simply "D" written on them that especially slow or misbehaving children were forced to wear while seated on a special stool in the classroom as a kind of shaming. Although I was in grade school long enough ago to have had a school principal who actually kept a leather strap in his desk drawer that he was not only legally permitted to use on children but positively encouraged to, I was at least a couple generations too late for the dunce cap.

This then got me thinking about dunce caps. For those of you too young or too innocent, dunce caps were tall conical hats with a "dunce" or simply "D" written on them that especially slow or misbehaving children were forced to wear while seated on a special stool in the classroom as a kind of shaming. Although I was in grade school long enough ago to have had a school principal who actually kept a leather strap in his desk drawer that he was not only legally permitted to use on children but positively encouraged to, I was at least a couple generations too late for the dunce cap.